This week, we bring you a Q&A with Michele Wales, Founder and Principal at InHouse Patent Counsel.

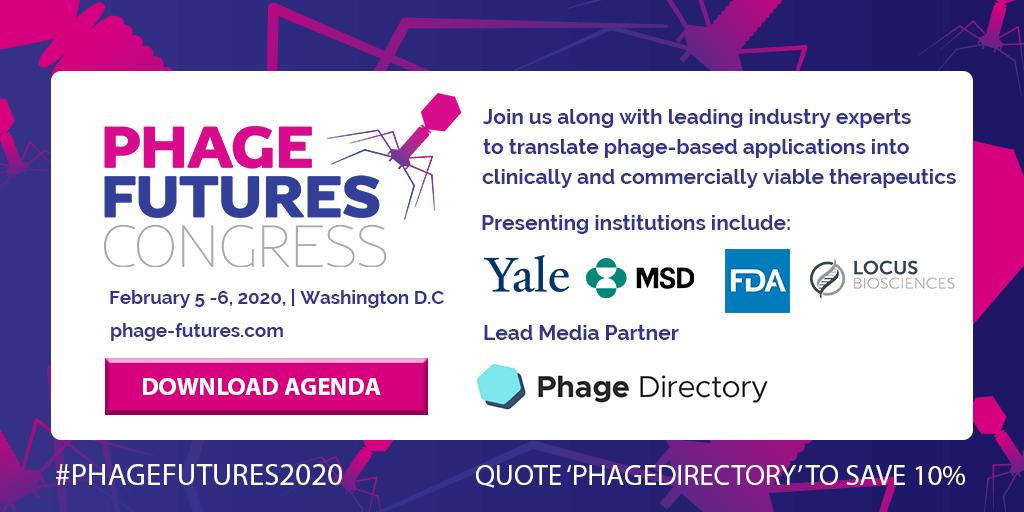

This piece was produced in collaboration with Kisaco Research.

Jessica: It’s really exciting to meet someone who’s on the legal side who’s also familiar with phages. There’s a lot of talk in the phage field about how important protecting phage IP is for incentivizing development.

Michele: Exactly. If you aren’t able to find a way to protect and patent phage technology, then why would investors invest money? How are they going to recoup their investments?

Have you worked with companies that are trying to tackle this and protect their phage IP?

Yes, I’m outside counsel for Adaptive Phage Therapeutics. They’re one of the companies developing phage as therapeutics to treat antibiotic resistant infections.

What was your background before that?

I have a PhD in Human Genetics from Johns Hopkins Medical School, and a JD from the George Washington Law Center. Over my career, I have focused on protecting biological therapeutics, such as DNA, protein, and antibody therapeutics. I worked for 15 years with Human Genome Sciences (HGS), where I ran their intellectual property (IP) and litigation department.

HGS was acquired by GSK about 7 years ago now, and at that point instead of going to a big law firm, I chose to start my own firm, where my practice concentrates on providing legal advice to emerging companies, mainly in the biologics field. These companies are generally smaller, less than 200, and maybe even less than 50 people, and normally don’t have any outside counsel. So I become very immersed in their business plan, their strategies, and how they’re looking to license and/or develop their IP portfolio, because IP is such a critical asset for them especially at the beginning. I work hand in hand with their CEOs, senior management and often their board to develop and then implement their strategy.

I also do a lot of public speaking on gene patenting, both in the US and internationally. To me, patenting a phage raises similar issues as when one patents a human gene.

My understanding is that patenting a gene came into question because of whether a gene is a natural entity or not. Is that the reason it’s similar to phages?

Yes. Since the 80s, the US was very strong on the patenting of human sequences. HGS was the “poster child” for this issue. And then about seven years ago the Supreme Court held that the patenting of a natural polynucleotide sequence, a sequence found in nature, was not patentable subject matter. Instead, the Supreme Court held in a case referred to as “Myriad Genetics” that the characterization of a new gene is just a discovery and not an invention. This decision changed the way the industry needed to protect DNA sequences.

But even though the Supreme Court held that DNA sequences found in nature can’t be patented, there are ways to “claim around” this decision. For example, claiming a sequence with non-natural sequences, such as expression sequences, can be deemed patentable subject matter. The expression vector isn’t found in nature — now it is patentable. So even though the Supreme Court made it clear that sequences found in nature can’t be patented, there are ways to get around it. The biotech industry can still thrive and exist.

Is this a little-known fact? Does the biotech industry realize this?

I don’t think investors always realize this. I think they get very nervous when a therapeutic product involves DNA, protein or antibody sequences. And I’m often asked to explain this conceptually to investors, so I guess it’s still a question. However, it is something that biotech lawyers know.

Can you protect phages by this logic?

So protecting phage has two main problems. The first problem is that phage are completely found in nature, so unless the phage are somehow further genetically engineered, for example if a portion of the sequence is removed, or a tag of some sort is added to the phage, you’re really going to have difficulty distinguishing the “therapeutic phage” from the phage found in nature. Therefore, protecting phage isolated from nature will be hard.

The second problem is because phage evolve so quickly, that even if you are able to patent a particular phage sequence, it would be very easy for a competitor to take that sequence and modify a bunch of nucleotides, and now it’s no longer the same phage sequence that is protected by the original patent. So for phage patenting, the two big hurdles are: one, the phage are found in nature, and two, the claims can easily be designed around by a competitor to escape infringement.

How might phage companies get around these hurdles?

So if you’re a company, you need to somehow find a way to give yourself a commercial advantage over your competitors. Examples of such advantages would be to protect methods of producing the phage in a highly purified fashion, methods of storing the phage, or methods of screening the phage for activity. Currently, the ability to identify therapeutically-relevant phage as quickly as possible is one place in phage process development where companies compete. If a company develops an assay that can generate a cocktail of phage to be used to treat a patient in six hours, where your competitors are doing it in four days, that’s something you’d want to patent. And so it’s a very different paradigm than protecting therapeutic proteins. Essentially you’re protecting methods that would be generic to all phage, and not phage-specific protection. This is the approach that I believe phage companies should consider.

We’ve been talking to a number of phage biotech companies, and we were surprised when some said it’s not a big concern if they get a phage and it changes over time, because they’re not thinking about patenting the phages. But still they’ve been trying to get phages from academic labs so they can screen them. And yet academic labs are thinking they have to patent their phages so they will be attractive to companies.

It sounds like the conversations you’ve been having are very consistent with what I’ve said. What are the companies you’ve talked to thinking, when it comes to how to protect their phages?

Engineering the phages comes up a lot. And the fact that they’re saying “we don’t care so much about the phage itself”, that their bottlenecks involve finding lots of phages to screen that are different from each other, and that they talk about plans to subject the phages to downstream processes, suggests that they plan to protect the processes rather than the phages.

Yes, that’s exactly what I was saying, it’s good that we’re consistent!

Do you consider yourself targeting a niche area that others aren’t exploring? Or are other law firms starting to think about phages?

Yeah, I think I’m niche, in a sense that I was in-house counsel at a company for a long time, whereas most law firm attorneys have only law firm experience. Because I was an executive at a company, I take a much different approach to the patenting than maybe my colleagues do. We’re always looking at a patenting question from a business standpoint — for example, does this make business sense to do and/or is this where you want to spend your money? I think that law firms often focus on billable hours and therefore it’s very easy to recommend, “hey you should patent the phage sequences”. And I usually am working with companies that don’t have a lot of money, and so we need to be strategic. And I think maybe that’s a difference that I bring to the table, because I’m looking at how do we get the biggest bang for our buck — how are we going to protect these natural products?

Are you feeling optimistic about phage companies having a fighting chance? It seems like there’s so many things stacked against any biotech, let alone one dealing with phages. Or do you see this as a situation where every field has its challenges, and this is just another one?

I think you’re absolutely right. Every field has its challenges, this is just the one that phage companies have. I think when you have challenges, it spurs innovation, and maybe in the past, people may have not spent money on manufacturing or process development; in this situation it’s money well spent, and who knows what type of innovation might come from it. It may not be straightforward, but that’s always the fun of it.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Further reading

Check out the four-part series we published last year on phage IP: