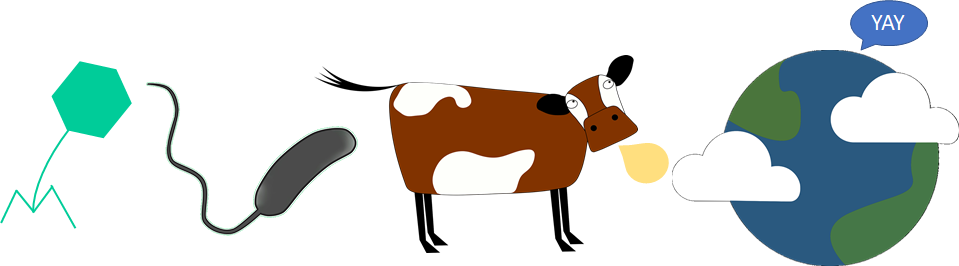

As someone embarking on a career in research and academia, I, like many other scientists, endeavour to carve a path I can follow and be passionate about. I have chosen the not-so-luxurious and rather foul-smelling rumen microbiome as the topic of interest. With this piece, I introduce this topic, list some of the questions that need answering, and hopefully convince you that, actually, the idea of using phages to help climate change might not be so far-fetched as it seems.

What is the rumen microbiome and why study it?

The rumen is the first chamber of the stomach system found in ruminants such as cows, sheep, goats etc. It is essentially a large anaerobic fermentation sack, home to a wide variety of microbes, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa and, of course, phages (and some other viruses). The microbiome is integral to the animal host, breaking down the fibrous grassy food to produce nutrients and energy. This is a complex process and has many variables, but ultimately ends with the fermentation processes producing CO2 and H2 which need to be dealt with.

This is where the archaea come in — methanogens are a hydrogen sink, taking these gasses and producing methane, which is eructed (burped) from the animal. Methane, as we all know, is a green house gas contributing to global warming. Whilst the archaea are therefore important, other bacteria, not so much.

Remember how I said that there are many variables? Well, the rumen isn’t exactly efficient, and depending on what you feed the animals, effects can be seen in not just methane production, but other wastes, such as nitrogen loss in the form of ammonia and urea, removed in the urine and polluting the fields they stand in. So, now you can see why studying the microbes and their functions might be important, especially taking into account the importance of ruminants in the future of the ever increasing human population.

What has been done before?

There has been ample research into looking for ways to control the microbiome to tackle methane emissions and efficiency, including feeding plant extracts, oils, antibiotics and many more. Phage therapy is one that always seems to be an aside, an “oh, by the way, this would be cool” addition to review papers. Yet, no one has really tried it, and there is very little in the way of publications on this. But this isn’t the only way that ruminants + phages = profit.

At this point, it’s possible to split research on ‘ruminants and phages’ into three parts:

- Phages as a part of the rumen microbiome.

- Using phages to treat or prevent pathogens in ruminants.

- The prospects of phage use in the dairy and livestock industry.

Phages as part of the rumen microbiome

This review paper pretty much sums up all the rumen virome research done to date. Generally, more work is needed here, and there are still lots of questions to answer (I go on to list some below).

Phages to prevent pathogens

It seems like most ‘ruminants and phages’ research that doesn’t focus on the virome looks at phage therapy for E. coli O157:H7. Known to cause bad gastrointestinal infections (probably an understatement) and even death in ruminants, it is also problematic for us humans. This is often seen reviewed together with phages in the livestock industry, but there was some fascinating research in 2003 that used the artificial rumen system to test their phages.

Phages in the dairy and livestock industry

This review paper nicely sums up the points in the dairy processes where phages could be or are being used. Probably more research is done in this area than is published, as a fair bit may well be hidden behind patents because of commercial aspects.

Conclusions

I want to study phages in the rumen, with the ultimate aim of using them to target bacterial species that make CO2 and/or H2 (which are used to make methane) and those that use up nutrients that are otherwise good for the animal.

As a starting point, I can look into phages + livestock pathogens, and phages + dairy.

Which questions still need answering?

I am more interested in the microbiome part; understanding the role of phages, and using them to manipulate the microbiome to have wider effects. There are many things that we need to answer before we can start chucking phages into cow tummies.

-

Phages have to be lytic, so which ones do we use? Do we have their genomes (probably important, right?)?

-

Which bacteria do we target? What functions do they have? Have we looked at their genomes?

-

What happens if we add phages into the rumen? How many? Do they ever meet their target?

-

Does the amount of CO2 and H2 decrease? Does methane decrease? Is this more efficient/is there less waste?

Plea for help

Has this triggered that lightbulb in your mind? Are you dusting off some info from an article you read and stored in the back of your mind? Or just have a bunch more questions? Please get in touch, I’d be intrigued to build this idea!

Papers linked in text:

My rumen phage publication can be found here:

The Isolation and Genome Sequencing of Five Novel Bacteriophages from the Rumen Active Against Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens

Rohit Kongari helped us produce this week’s article by helping us source and write the What’s New section. Thanks Rohit!!

Interested in becoming a Phage Directory volunteer?

Email [email protected].