This article is part of the ‘Phage Australia Lab Series’, where we’ll be sharing the work we’re doing at Phage Australia. Check out our last post, where Stephanie Lynch wrote about how we sent a phage around Australia and asked everyone to titre it!

I’m writing this post partly for myself, to get my thoughts organized (I’m pretending you all are my virtual labmates!) but also, I think it could be helpful for others. I hope others see my process, send me helpful tricks / point out where I’m missing something, and hopefully get inspired to wrangle their own lab chaos and/or make phages for themselves!

Of note, Ali Khalid, PhD student in the Iredell Lab and Phage Australia team member, with the help of Helene Lebhar at UNSW’s Recombinant Products Facility, has done a huge amount of work getting our phage manufacturing off the ground. What follows is my perspective on getting myself organized so I can help extend Ali and Helene’s work to bridge some of our current gaps.

Patients are waiting on us

First, some context on why we need these phages, since of course, that will drive a lot of our decisions. At Phage Australia, we need phage. Not just any phage, but safe preps of phage we can use in patients. Here in Sydney, we’ve got three patients ready to be treated — they are just waiting for their phages.

The trouble is, we aren’t fully set up to make phages yet. We are still in the pilot phase of this work, and the funding for our own GMP phage-making setup that we can scale has yet to come in. Sure, we could get phages from other people, but the whole point of Phage Australia is to develop this capacity for ourselves.

While we wait for the grant (fingers crossed!), we need a system that works now so we can respond to cases that come in, and in the process, prepare to scale up and certify our process once we do get the funding.

Making phage is simple, right?

I came into this feeling pretty confident I could make this work. There are tons of ways you can make phages. Tons of papers written about it. Lots of people make phages. You just need a flask, right? So I set out to find a phagemaking protocol. My strategy was to pick a few groups I know are making phages regularly, to roughly the standards we need (US FDA, emergency/compassionate use), check out their most recent papers, and do what they do.

Quickly I realized everyone does things slightly differently. Ok, no problem, I thought, I’ll test a few things and whatever works best, and is easiest, that’s what I’ll do. But what does ‘best’ mean? What does ‘easiest’ mean? Which steps can I skip? Which pitfalls do I want to avoid? I descended down a rabbit hole of things that could matter. It seemed like each paper highlighted why their method was better than the others. And I didn’t have the materials to try everything. Or the time. Suddenly, this did not feel like a simple task. I felt like I had a thousand decisions to make. For instance, how much phage to cell ratio do you use? When do you add phage? How long do you let it incubate? Will more aeration be good for the phage or bad? Should I spin down after 5 hours, or wait until the next day?

And that’s just making the phage. Then there’s purifying it. Some use cesium chloride, while others say that’s an old, crude method that brings in dangerous chemicals. And it’s a pain to set up — careful not to disturb the gradient! Others use organic solvents, or ultrafiltration… Cytiva, Sartorius, Akta Flux, ion exchange, polishing, buffer exchange. So many new words to learn, each with specifications and pore sizes and capacities.

Case in point, I quickly went from ‘this is straightforward’ to option paralysis. What I thought was an opportunity (I get to design this from the ground up! No biases! First principles!) started becoming a dizzying array of options, with no place to start.

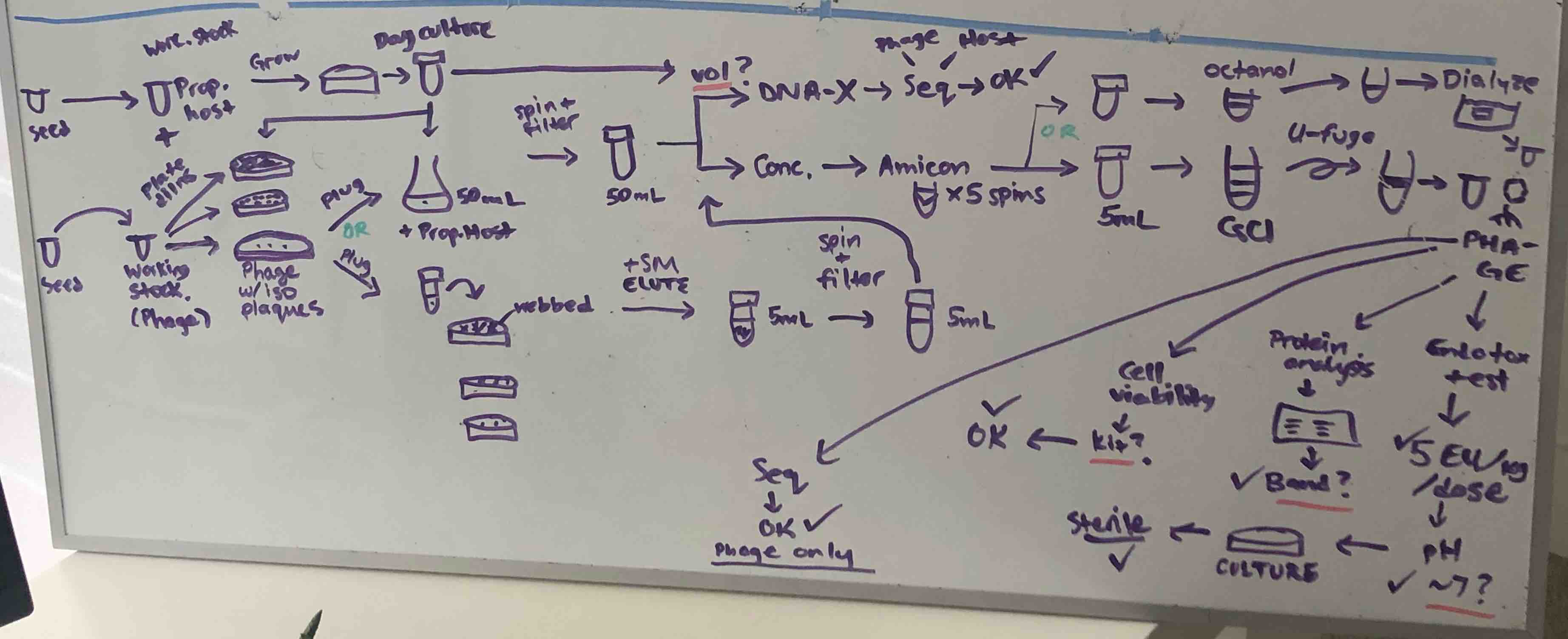

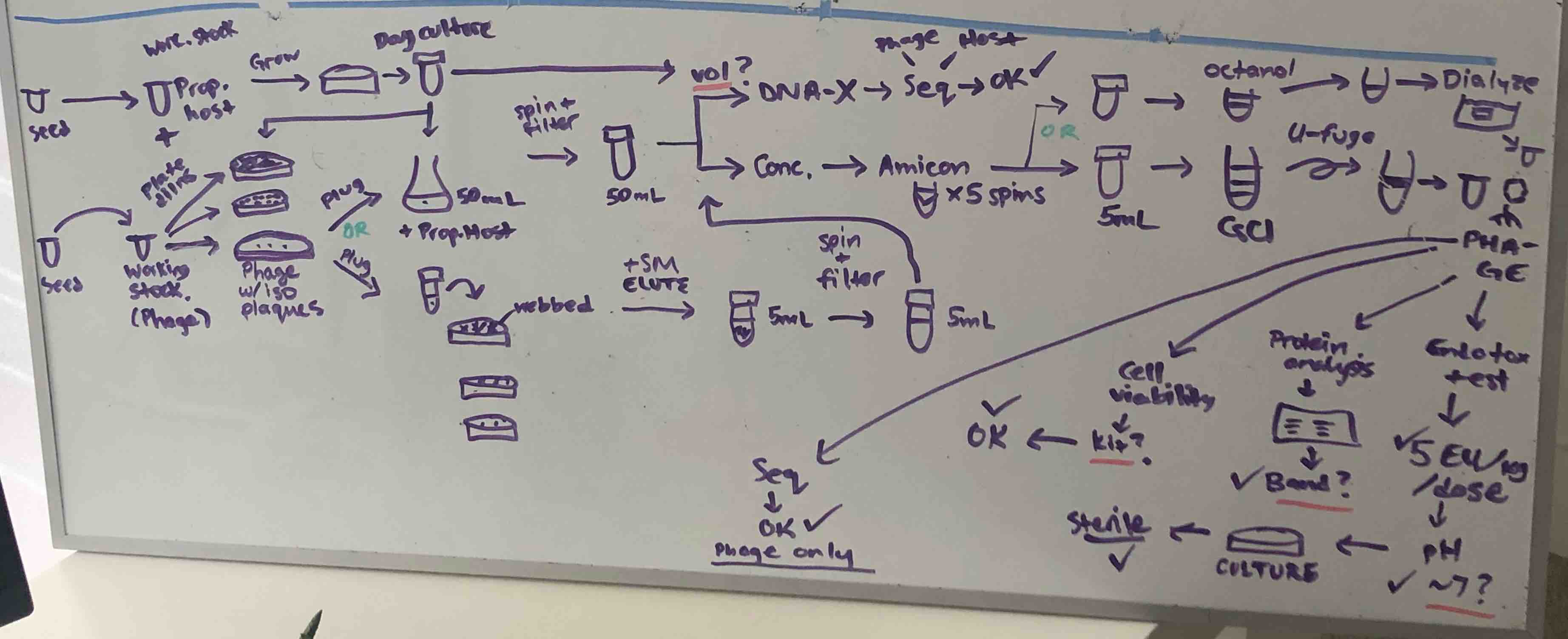

A snapshot of what my brain was trying to keep track of as I thought about how to get a minimally functional phage-making system up and running.

Start with the end in mind (figure out what we’re optimizing for)

To give myself somewhere to start, I took a breath and thought, ok, what are the actual things we need? What are we optimizing for? What are our constraints?

To address our imminent patient needs, our needs are actually simple. We need enough phages, and we need them to have low endotoxin to be safe. And right now, we have limited time and materials.

Our needs

- Enough phages

- Safe phages

Our constraints

- Limited labour time

- Limited ability to order new equipment

What is enough?

Phage Australia has a protocol for phage therapy called STAMP (recently approved and started recruiting/treating patients earlier this year). In it, dosing is standardized: 10^9 PFU per dose. Minimum 28 courses of that. So we need minimum 2.8 x 10^10 phages for each patient. Let’s aim for some wiggle room, and try to get 10^12 phages per patient.

What is safe?

We know how low the endotoxin content needs to be (FDA has guidelines, and Australia will likely follow this: you can only put a max of 5 endotoxin units per kg/h into a patient’s vein). So that means we’re successful if we can get below maximum endotoxin concentration (5 EU/kg/h, meaning for a 70-kg patient, we should aim for below 350 EU per phage dose).

Limited personnel and equipment

We only have two postdocs devoting part of their time to this, so phage-making should be doable in about 20 person-hours or less per week. And since we’re in a relatively isolated country in the middle of a global supply chain crisis, trying to stretch the grant dollars we have until the end of the year, let’s try to limit ourselves to things we have in the lab, and avoid ordering anything new.

Decision: let’s optimize for making enough safe phages easily, using what we already have.

Identify the core components of the work

At its core, we need to make a bunch of phages, and remove the endotoxin. Next let’s break it down further. What does each step entail? How do we know if it’s successful?

1. Phage production

- Grow phage and cells together

- Separate out the phage

Successful if: we achieve our minimum per-batch phage amount (10^12 PFU)

2. Endotoxin removal

- Concentrate the sample

- Remove the endotoxin

- Get rid of anything dangerous you added to get rid of the endotoxin

Successful if: we get below maximum endotoxin concentration (5 EU/kg/h, ie. 350 EU per 10^9 PFU)

Note: endotoxin removal is more than just endotoxin removal

I have identified at least two shadow steps that come before and after the actual removal of endotoxin: concentrating your sample beforehand, and cleaning it after. Most endotoxin removal steps I’ve looked at require a concentrated phage solution before moving to endotoxin removal. For example, CsCl gradients call for adding ~3 mL phages, meaning no matter how much phage you make, you need it to be concentrated into 3 mL if you want to use CsCl. Another option is octanol — for this step, you’re adding octanol approximately 1:1 to your phage. Unless you want to go through litres of octanol, you’ll want to concentrate your phage ahead of time. Then, after endotoxin removal, you need to remove whatever you added to remove the endotoxin that might be toxic (e.g. cesium, octanol).

Look at our options for each step

For each step, there are many ways you can do it. I found it helpful to list the options/considerations for each. I found ideas by reading a few papers from friends in the phage field I know make phages for compassionate use cases, like TAILOR, IPATH, and the Phage on Tap method, developed by one of our own Phage Australia colleagues.

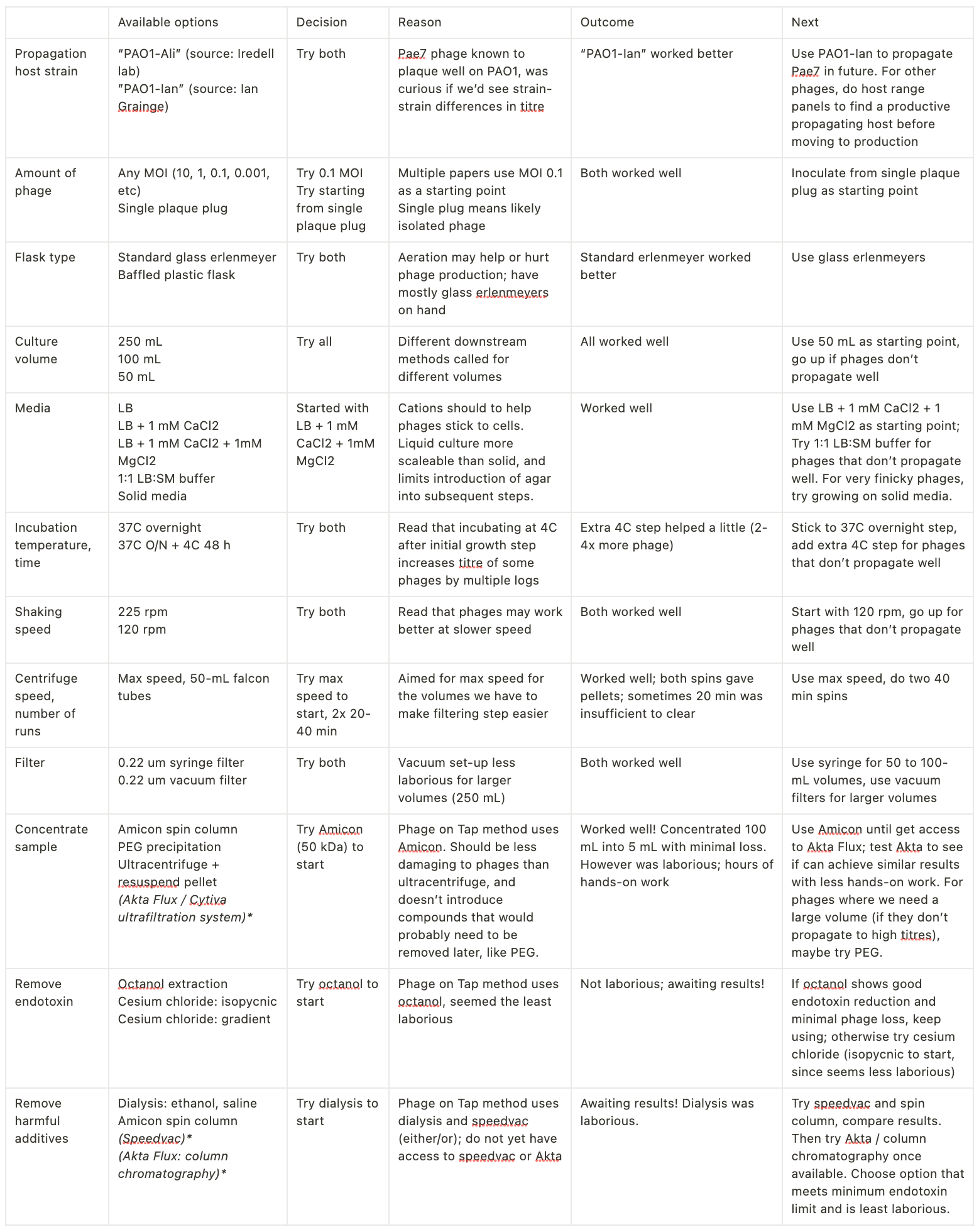

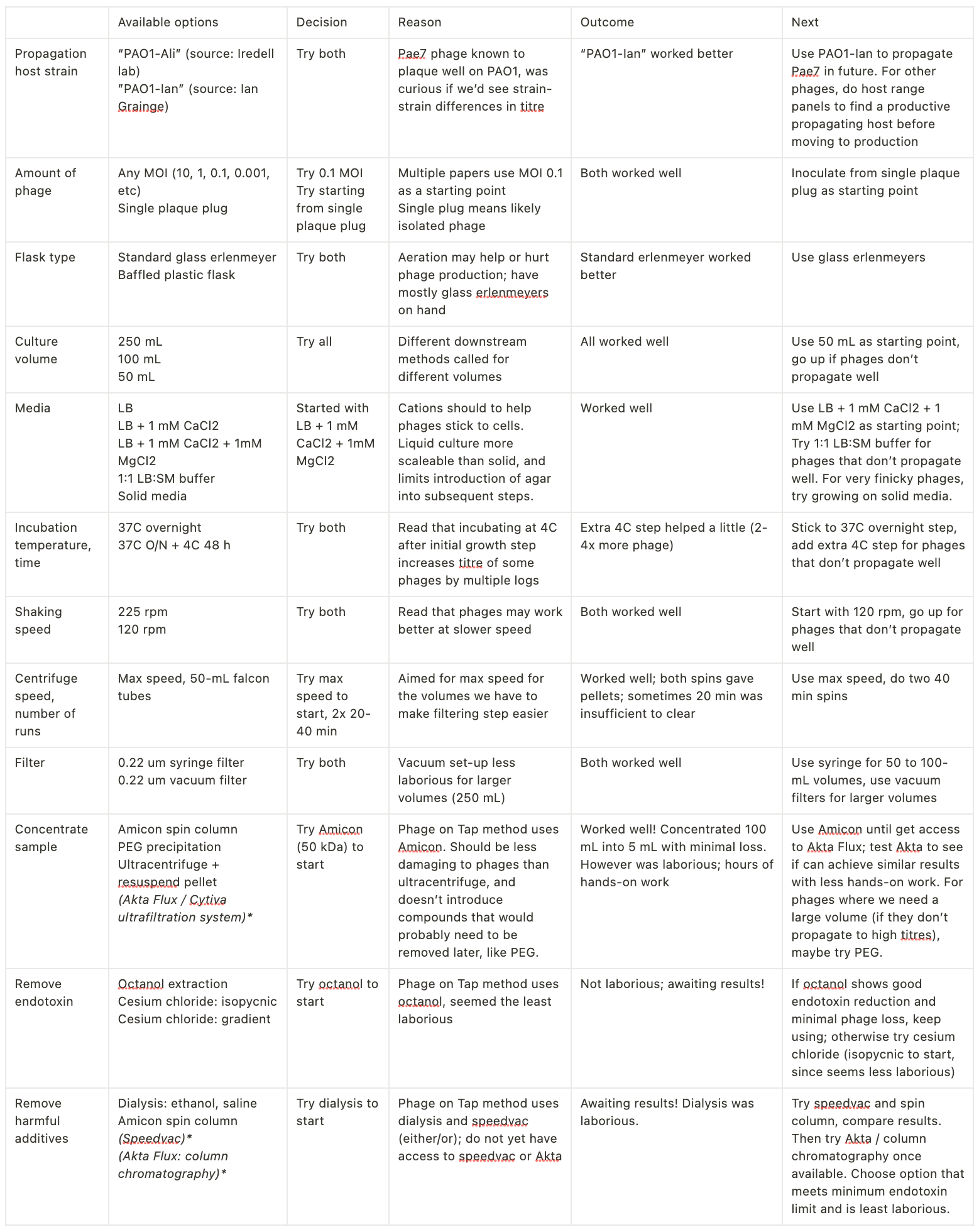

Decide what to do at each step, and document why

Next: deciding what to do for each step. To illustrate my thought process and how/why I’m making these decisions, I started laying this out in a table, along with what I’ve tried to date. For each step, I picked one approach (the easiest option available).

Minimize optimization creep!

Even though I thought I knew what I was optimizing for, I found that my instinct was to get into the lab and start optimizing everything, setting up little parallel experiments here and there ‘just to see’. I found that I was constantly trying to optimize for the highest titre, even though that is NOT what I decided to optimize for. It took me a while to realize this was happening, and I still have to catch myself constantly and resist that urge.

I came to realize that while there’s a lot we COULD optimize, we shouldn’t try to do this. It would make the task at hand take forever, most likely overwhelm us, and ultimately not help us achieve our goals (patients getting enough safe phages fast!). Hence why I found it helpful to get very clear on what I was optimizing for, then look at all my options through that lens. Given I decided we’re going for ‘good enough’, (ie. enough phages, safe enough), that means if a step meets that minimum (ie. we look like we’re on track to hit at least 10^12 phages at the end), we move on. Of course, if in the future we use a phage that doesn’t propagate well, or purify well, then that would be grounds to start tweaking the steps prior to that point. Otherwise, we’ll move along.

Of note, most of my work so far has been with two phages, Pae7, a Pseudomonas phage, and Ec134B, an E. coli phage. I fully anticipate things to change with different phages. I’m hoping we can at least find a baseline that works pretty well for lots of phages, then tweak from there when we need to (and only then).

A few more notes, learnings, questions

Getting high enough titres

For a while I wanted to achieve higher titres so I could skip or reduce the need for a concentration step prior to endotoxin removal (I’d heard it could be an annoying bottleneck). I played with a bunch of temperature, flask, time and media parameters, which didn’t affect production by much (max about half a log). For now I’ve deemed most these kinds of tweaks to the growth step not worth doing.

For example, leaving cells+phage together for the weekend at 4C before filtering out the cell debris led to 2-4x more phage, which I felt wasn’t enough of a jump to justify the extra time and unknown effects on the phage that that extra step would bring. Going forward I think we should just focus on choosing a good host strain, letting the phages grow to the titres they get to using standard conditions for that strain, and being ok with having a concentration step.

If phages are finicky, switching to solid media is something I think will help a lot to increase titres (we haven’t gone there so far, since others in our group have seen agar cause problems downstream, but I still think this could be a reasonable tradeoff if the phages won’t propagate well in liquid).

The one thing that worked the best to improve titres was changing out the propagation strain (led to about a log increase). Based on this, I think doing a host range panel to make sure we’re using the best strain we have for that phage would be worth the effort.

Getting rid of endotoxin

So far I’m happy with the amount of effort that octanol required (other than the dialysis step which I’d like to replace, since it was fairly laborious and used litres of ethanol). It will be interesting to see if it’s sufficient to remove endotoxin without removing too much phage. Jonas Van Belleghem and colleagues have done a really nice study contrasting different endotoxin removal methods, and octanol seems to be a reasonable choice (though it of course depends on the phage). (We have a large amount in the lab right now, and it only took a few mLs to do an extraction, though I’ll need to check how much it is to replace).

Beyond that, I want to try CsCl; first, gradientless (I only recently found out you don’t always have to build a gradient, thanks to Sabrina Green at TAILOR!) (her Youtube video and protocol here). The trouble is this method calls for a refractometer to measure density, but we don’t have one. I may try without (I’ve also found this protocol by the Center for Phage Technology which seems to do this). If that doesn’t work, I’ll do the gradient. Who knows though, we may get our Akta Flux (along with some chromatography columns), before I have the chance or the need to try CsCl.

Concluding thoughts

Thanks for reading! I hope you can take away from this that a complex array of options in the lab can be simplified into a path forward. The way I’ve found is helpful is:

- Decide what you’re optimizing for (what would success look like?)

- Break the project into its core components

- For each core component, make a list of what your options are

- Filter for materials you have access to

- Make a choice of one thing to try first for each step (and document why!)

Ultimately you should have one thing to try for each core component of your process. I decided not to order anything new, then picked what seemed like the easiest thing of the options I had available. I resisted the urge to do everything in parallel and compare based on which gave the highest titre (I was only able to resist this urge once I got clear on what I was optimizing for: hitting a minimum phage titre, the easiest way possible; NOT maximizing phage titre). I found it helped to make a table, then to force myself to list the core function of the step, the options I had available, the decision of what to try first for that step, the outcome, and the next step.

What felt before like a dizzying mess now feels like a framework I can build on. As I come across new options, I can look at my table and ask myself, is this new option going to be less laborious or ‘better’ than what I’m already doing? What evidence do I have for that? Importantly, is it ‘better’ according to my predefined success metric, or am I starting to optimize additional things I don’t need to optimize? (Beware optimization creep!)

Anyway, I’m happy with this framework for now — I’ll see how it serves me! Would love to hear others’ thoughts, helpful methods you’ve used to manage complexity in the lab and avoid option paralysis, as well as any specifics or magical phage-making tricks I’ve missed here!

Resources that helped me

Acknowledgments

- Stephanie Lynch, my co-pilot here in the Iredell lab — we’re both closely working on all of this, trying to navigate doing our work as a team rather than as individuals; I could not imagine a better lab co-pilot!

- Ali Khalid, who’s been working on purification of phage with Phage Australia for the last several months, and has helped me get up to speed on what it can entail. I’ve learned a ton from what he’s done, and he’s helped me get this all straight in my head.

Thanks to you readers for being my virtual labmates!

My dream would be that scientists everywhere would blog about the work they’re doing, the decisions they’re making and why, so we can all learn from each other’s thinking and experience. In my mind there’s no good reason not to. It’s not like one’s blog musings about why they ultracentrifuged at one speed vs. another are going to prevent journals from accepting our papers.

If we’re worried about looking stupid, well, I guess that’s the only risk left. I definitely was when we started Capsid & Tail 3.5 years ago. But as I’ve found from putting out the newsletter/blog every week since, and getting told exactly zero times that I’m stupid, I’ve realized it’s probably not that big a risk to say things online, without the shield of peer review and co-authors. You should try it! (Conveniently, we have a guest writer program for C&T!)

For more on why you should share what you’re working on as you go, check out this great article on how publishing your thoughts increases your luck. It inspired me to write this this week!